“Death of a Salesman” is the best-known play by American playwright Arthur Miller, one of the great figures of American literature in the 20th century. This work, premiered in 1949 to great acclaim from critics, tells us the story of Willy Loman, a 63-year-old salesman in mid-century New York, who has had rather limited success. Despite this, he has always extolled the virtues of capitalism and has worked to instill in his children the values of hard work and sacrifice, still believing that all his efforts will eventually be rewarded.

The play focuses on the final days of this character, when due to his advanced age, he begins to suffer hallucinations that make performing his work terribly risky. When he goes to ask his boss for a position that doesn't require driving, appealing to his loyalty to the company and the immense amount of time he has dedicated to a business that wasn't even his own, he is fired. This event leads him to suffer even more severe hallucinations, and ultimately, Willy ends up committing suicide so that his family can collect his life insurance policy.

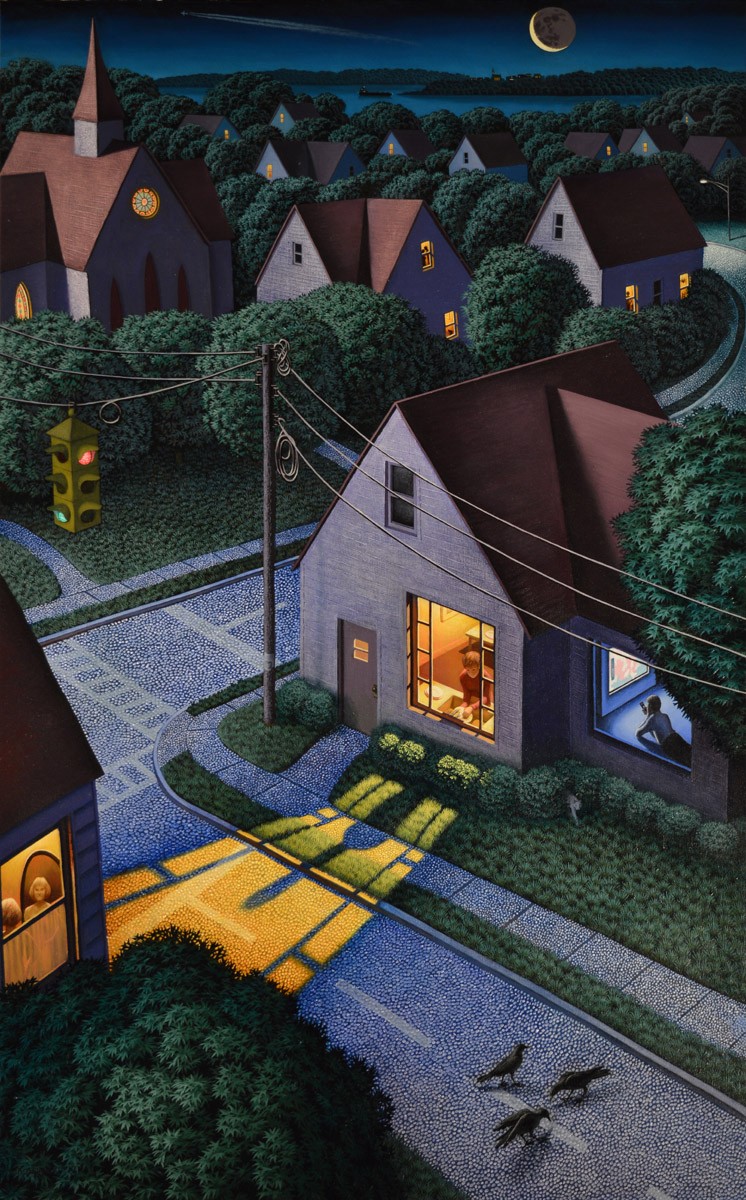

Death of a Salesman (1951), Laslo Benedek.

A significant portion of the audience criticized the play's clearly anti-capitalist bias. In a period where the USA had emerged as an unparalleled world power save for the USSR, and was exporting the American way of life to the old world through the Marshall Plan.

This piece constituted an attack on all those ideas that drove the gears of the capitalist machinery of Fordism, and by extension, a direct attack on the beating heart of the USA as a nation, on the idea of the American Dream.

Ford factory in Minnesota

In the play, we see a fierce critique of this meritocratic notion, which devours everything in its path and discards those who no longer serve it, yet still has faithful and devoted followers, and continues to be thought of in the collective imagination as a reality. Willy Loman truly believes in this idea, he lives his entire life through the lens that it offers him, and he even instills these notions in his children, so that they may become someone in life.

But as the years go by, this death of the American Dream, this exposure of the artifice it represents, has mutated to adapt to a society that increasingly sees it as less true.

And of all the cultural pieces that represent it as such, perhaps the animated series “The Simpsons” is one of the most accurate.

The series follows the Simpson family, a representation of a standard middle-class American family. Although the series doesn't have a protagonist per se, one of the characters around whom most of the plots revolve is Homer Simpson, the patriarch of the family. Homer is a middle-aged man who was forced to start working at a nuclear power plant when his college girlfriend, Marge, accidentally became pregnant. By the time the series takes place, they have already had three children, and Homer remains trapped in his same old job.

Although the series canon is lax and confusing, we know that the life Homer leads now is a disappointment to him, as he dreamed of being a rock star. The alienation caused by a job he detests is not fulfilled by family either, as he verbally and physically abuses his eldest son and spends most of his free time in the bar, indulging a habit of alcoholism that he uses to mask the disappointing nature of his existence.

Ford factory in Minnesota

And here is where we see the greatest differences between both cultural pieces. While Willy Loman works tirelessly in pursuit of the American Dream, which promised him success if he was willing to make the sacrifice, Homer is barely moved by such ambitious motivations, simply using the job to have a livelihood and means of support.

While Willy makes sure to instill capitalist society values in his children, Homer doesn't even bother to uphold these values himself, and the tendency seen in the series leans more towards apathy.

If in “Death of a Salesman” we saw the American Dream as an idea that moved people, even if it ultimately betrayed them, in “The Simpsons” we see the next logical step: an American Dream that no longer presents itself as such.

The system has no alternative, there is no mirage of progress that illuminated the futures of mature Fordist America, and without the physical capacity to imagine new horizons, what remains are the same remnants but marked with the stigma of apathy, dragged through life without dreams or ambitions.

Queue of beggars during the Louisville flood, 1937, taken by Margaret Bourke-White.